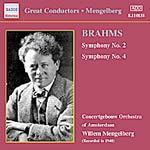

Brahms: Symphonies Nos 2 & 3 (1941 recording)

$25.00

Out of Stock

$25.00

Out of Stock6+ weeks add to cart

JOHANNES BRAHMS

Brahms: Symphonies Nos 2 & 3 (1941 recording)

The Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam / Willem Mengelberg

[ Naxos Historical Great Conductors / CD ]

Release Date: Thursday 15 November 2001

This item is currently out of stock. It may take 6 or more weeks to obtain from when you place your order as this is a specialist product.

"Ward Marston's transfers are the finest now available of these recordings...If you want Mengelberg's Brahms 2 and 4, Naxos' bargain price and superior transfers speak for themselves." ClassicsToday

Willem Mengelberg's tenure as Music Director of the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra dates back to 1895, when he not only succeeded its founder Willem Kes, but also appeared with them as the soloist in Liszt's Piano Concerto No.1. It became one of the great musical partnerships of the first part of the last century. After only three years at the helm, 'Mengelberg's orchestra' famously won the dedication of Richard Strauss's Ein Heldenleben. The New York recording of that work made in 1928 and shortly to be issued as part of the present series remains an unsurpassed touchstone, and his legendary 1920 Mahler festival in Amsterdam proved to be a landmark event in the history of the composer's performing tradition.

As well as revealing fascinating insights into the distinctive qualities of Mengelberg's conducting style, the readings featured on the present release also offer invaluable documentation, both of the interpretation of Brahms and of the orchestra's evolving history. Although there are no alternative live Mengelberg recordings of these particular works, as is the case with the First and Third Symphonies, the attentive listener will encounter performances that are characteristically athletic and powerfully wrought.

The great generation of Brahms conductors that succeeded the composer's favoured contemporaries, Hans von Bülow and Fritz Steinbach, included both Wilhelm Furtwängler and Arturo Toscanini, and it is striking to hear Mengelberg steer a middle course between the disciplined rigour of the Italian and the intense visionary drama of his German counterpart. Although Mengelberg had a reputation for loquacious rehearsal techniques, his meticulous preparation paid huge dividends in the expressive flexibility and emotional penetration that he brought to bear on both works. Unlike his Tchaikovsky interpretations, for example, there is little evidence here of his notorious 're-touchings'. Nor does he subject the music to the extremes of subjective hyperbole that we readily associate with Leopold Stokowski, perhaps the conductor with whom Mengelberg's questing brand of recreative spirit is most closely aligned. Mengelberg focuses primarily on sympathetically integrated tempi, lyrical and beautifully sung phrasing, and a transparency of orchestral texture that trounces any suggestion of impenetrable scoring. The tiny Luftpause that peaks around the big soaring violin melody in the first movement of the Fourth Symphony is the only major idiosyncrasy, and not one that is unduly disruptive or redundant, merely rather waggishly in keeping with the arch of the phrase.

The music is never fussed, cajoled or over-studied, but unfolds with spontaneity and irresistibly clear logic. The wonder is that although every bar teems with action and nuance, the overall symphonic purpose and direction are expounded with compelling grasp, both within individual movements and, even more crucially, within the work as a whole. This allows a romantically inflected dramatic tension to grow and develop within a classically realised framework that tellingly reflects the composer's studies of Bach and his precursors. The counterpoint of inner lines, whether on strings or woodwind or as chords among the brass, is revealed with lucid perspective and balance. The significance of Mengelberg's annual Palm Sunday performances of the St Matthew Passion that started as far back as 1899 is salutary. Few conductors reveal and refresh the archaic modality of the Fourth Symphony's second movement with such stylistic aptitude and resonance, and the mobility of the bass line throughout the various statements of the last movement's passacaglia theme renders the headlong rush to embrace disaster inevitable.

The spectre of war, which was imminent when the Fourth Symphony was recorded and already in full cry while Mengelberg was setting down the Second, possibly played a part in generating additional adrenaline. The Fourth is tinged with a profoundly sad and almost desperate gravitas, while it is not too fanciful to detect an almost defiantly sunny disposition and protesting optimism in the articulation of the Second. The triumphant conclusion certainly rings out with intoxicated affirmative fervour.

It is well known that, following the occupation of Holland, Mengelberg accepted a post in the Nazi Culture Cabinet and many Jewish personnel in the Concertgebouw Orchestra were removed. Notwithstanding counterclaims of naivety and the help given by the conductor to individual Jewish musicians, Mengelberg became the butt of widespread vilification. His wartime affiliations had extended beyond an administrative rôle to guest engagements in Germany with the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonic Orchestras. He was dismissed from the chief conductorship of the Concertgebouw Orchestra in 1945 and withdrew ignominiously to Switzerland, where he lived until his death in 1951.

The Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra has always been a particularly tradition-conscious body of players. Even in relatively recent times, its resistance to certain areas of repertoire has made musical headlines. Its special sound quality was zealously nurtured and guarded as part of that tradition, and never more productively than under Mengelberg's influence. Until the Second World War it manifested a wholly distinctive and instantly recognisable sound profile, one that is engagingly audible in these Brahms performances. The strings possess a muscular, sinewy tone that never swamps the texture, allowing other sections to variegate colour when necessary and notably different to the saturated dominance cultivated by many Brahms conductors in the second half of the twentieth century. Lyrically pliant, soaring and graceful, but with gutsy emphasis when required for more forceful passages, the sound is delicate, radiant or powerful on demand, with portamento sparingly (but judiciously) voiced for pertinent added emphasis at key moments.

Similarly, the woodwind is a collective of characterful soloists, lithe, reedy and plangent in isolation, and an athletic, well-integrated choir as an ensemble. Their interplay with the strings in the darting third movement of the Second Symphony is a miracle of articulation and of musicians pertinently listening to each other, the acoustic of the hall audibly played off for all its considerable worth. Perhaps most striking of all is the sonority of the brass tone, particularly that of the trombones, whose burnished, cutting edge remains unique. Brahms deploys them sparingly but tellingly, and the Amsterdam players never fail to respond with a characteristic dark-hued profile.

Partnerships of this quality and duration between conductor and orchestra have become rare in our times. Not only do these performances sound a corrective to late twentieth century blandness and indulgence in Brahmsian symphonic interpretation, they also represent a signal testament to the special achievements of a long term creative alliance.

Tracks:

Symphony No.2 in D major Op.73

01. Allegro non troppo 13:10

02. Adagio non troppo 09:33

03. Allegretto grazioso 05:11

04. Allegro con spirito 09:13

Recorded: 1941

Symphony No.4 in E minor Op.98

05. Allegro non troppo 12:29

06. Andante moderato 11:49

07. Allegro giocoso 06:22

08. Allegro energico e passionato 09:51